Key Takeaways

- “Hangry” describes the emotional state where hunger leads to irritability, anger, and reduced emotional control, largely driven by low blood sugar and hormonal changes.

- Rising ghrelin and falling leptin during hunger weaken emotional regulation, increase stress sensitivity, and reduce patience and focus.

- Hunger activates brain regions involved in emotion and threat detection.

- Hangry episodes can be reduced by eating protein- and fibre-rich foods, staying hydrated, maintaining regular meals, and getting enough sleep to stabilise hunger hormones.

What Is Hangry?

“Hangry” is a portmanteau of hungry and angry [1]. It is used colloquially to refer to people who become angry when they get hungry. Low blood sugar levels in the bloodstream are usually attributed to the feeling of hangry.

How Hunger Affects Our Mood

The two key hormones involved in hunger regulation are ghrelin and leptin [2].

1. Ghrelin

Ghrelin is made in your stomach, and its job is to nudge your brain whenever your stomach is running on empty. As mealtime gets closer, ghrelin levels rise, which is why you start feeling restless, distracted, and sometimes snappy. After you eat, ghrelin drops again, and your mood usually settles.

That rising signal can make your emotional regulation weaker, so you react faster, feel more stressed, or get annoyed by things that normally do not bother you.

2. Leptin

Conversely, leptin works on the opposite side. It is made by fat cells and acts like a regulator. When leptin is higher, your brain knows you have enough stored energy, so your appetite goes down. When your body fat decreases or when you go long periods without eating, leptin drops.

Lower leptin means your brain thinks you need energy right now. This can make you more sensitive to stress, more impatient, and less able to think clearly or calmly.

Why does this affect your mood?

When ghrelin rises, and leptin falls at the same time, your brain becomes more reactive and less steady. That is why hunger affects:

• irritability

• focus and mental clarity

• stress tolerance

• patience

• emotional stability

Your brain is powered almost entirely by glucose, so when energy dips, it goes into survival mode. That means prioritizing food and reacting quickly, not staying calm or compassionate.

Is Being Hangry Real?

So, we’ve answered the question of “What is hangry?”, but is being hangry real or just an excuse for bad behaviour?

Yes! Being hangry is a real thing. In a study conducted in 2002 [1], it was found that over a period of three weeks,

- 56% of the variability and irritability their participants felt was due to hunger

- 48% of the anger experienced was caused by them feeling hungry

- 44% of the pleasure they felt was due to hunger

The study also found that the levels of hunger / low blood glucose can greatly impact the feelings of anger and irritability. Additionally, their results found that negative emotions–irritability, anger, and lower pleasure–were predicted by both day-to-day fluctuations in hunger, as well as mean levels of hunger over the previous three weeks [1].

This conclusion has also been supported by other small bodies of research, which affirms that the emotions induced by hunger (hangry) have shown participants to be more “impulsive, punitive and aggressive”, [3] when they have not eaten.

Why Am I So Hangry?

What is “hangry” doing to your mental state? Well, being hangry, which is a state of being hungry, is known to affect emotions and judgments in many people. When deprived of food in different situations, there is an inherent increase in motivation to engage in a more persistent and aggressive behaviour to secure food resources [1]. As such, this aggression may stimulate negative feelings like anger, irritability, and rage.

Causes

Low blood sugar also stimulates the release of ghrelin, a metabolic hormone that signals hunger. Ghrelin activates a hormonal cascade that includes cortisol. Cortisol, the hormone that is known to be the “stress hormone”, colloquially stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, which produces high arousal bodily changes such as increased tension, heightened alertness, and reduced emotional stability [3].

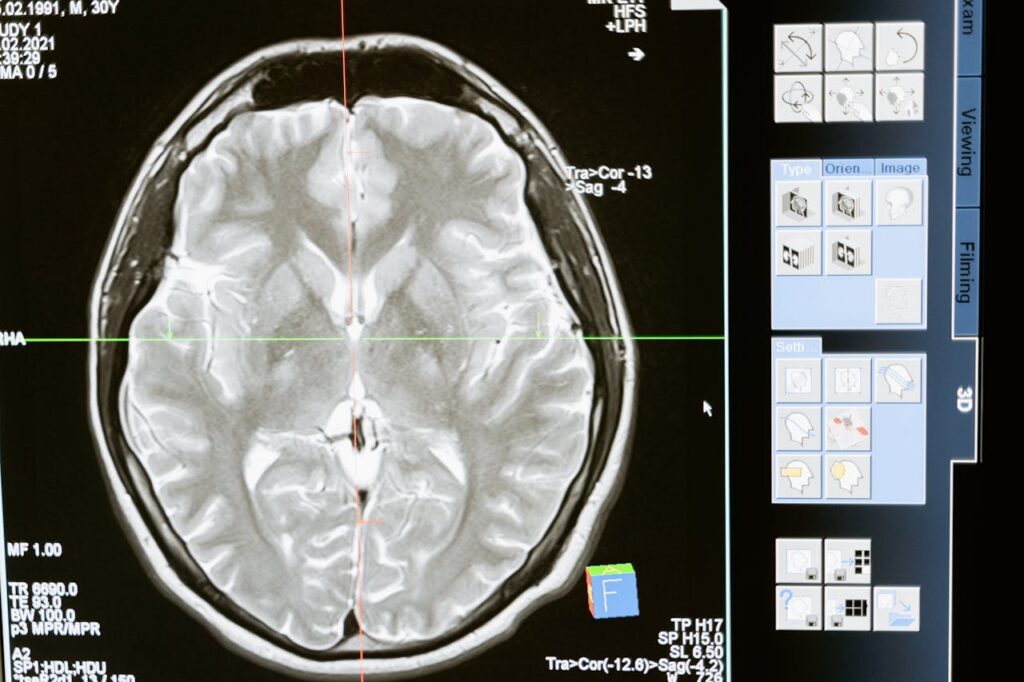

Additionally, neuroimaging studies found that specific brain regions show increased activation during hunger. These specific brain regions are the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and amygdala [3]. They become more responsive under low energy conditions and are strongly involved in emotional regulation, threat detection, and the integration of bodily sensations.

Consequently, if the brain regions increase activation in those areas, there will be more emotional reactivity and less tolerance to any stressors [1].

How to Manage Being Hangry

1. Eat food with high levels of satiety

Across 14 short-term studies [4], 11 found that higher protein preloads significantly increased subjective satiety. In addition, 8 out of 15 studies showed that individuals consumed less energy in subsequent meals when they had eaten a protein-rich preload. Protein preloads in these studies ranged from 29 percent to 100 percent protein, compared with carbohydrate or fat-based controls. Include high-protein foods such as eggs, Greek yogurt, tofu, fish, poultry, or beans in meals and snacks to prevent abrupt hunger-related emotional shifts.

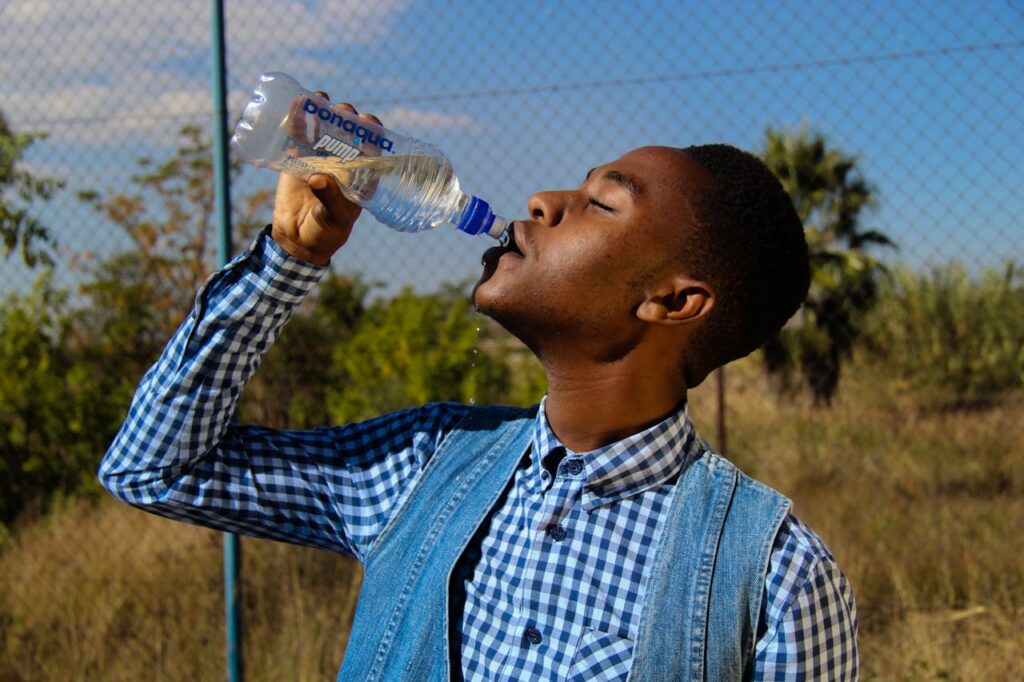

2. Drink more water

Hydration influences appetite regulation, but research shows that liquid foods, especially soups, have an even stronger effect on satiety than water alone. Foods with higher water content create more stomach distension. This activates stretch receptors in the stomach, which enhances satiety signals to the brain.

The study by Rolls et al. (1990) [4] examined how different energy-matched preloads affected later food intake. Participants consumed one of the following before a meal:

- tomato soup

- melon

- cheese with crackers

All three options contained the same total calories. Despite that, their effects on appetite differed.

- Soup reduced subsequent energy intake the most.

- Participants ate fewer calories at the next meal when the preload was tomato soup. This indicates that soup provides a greater feeling of fullness.

- Energy density was not the only factor.

- Cheese with crackers had the highest energy density, yet it produced the weakest satiety effect. Melon and soup, which had lower energy density and higher water content, performed better.

3. Eat more fibre

What is “hangry” and fibre’s relationship to each other? Based on a study by Duncan et al. (1983) [4], the energy density of a diet was examined with regard to the calorie intake and fibre content.

| Diet Type | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| High-energy-density diet | high in fat and sugar, low in fibre |

| Low-energy-density diet | high in fibre, low in fat |

Key Findings

a) Participants consumed half as many calories on the low energy density diet.

The high fibre meals provided greater volume and slower digestion. This allowed participants to feel satisfied while consuming far fewer total calories each day.

b) Eating time increased by thirty-three percent on the low-energy-density diet.

High fibre foods require more chewing and slow down the meal pace. Longer eating time increases satiety signalling through the brain’s appetite regulation pathways.

c) Fibre played a central role in lowering energy intake.

High fibre foods add bulk without adding many calories. This increases stomach distension and strengthens fullness cues. By contrast, high-fat and high-sugar foods pack many calories into smaller volumes, which increases the likelihood of overeating.

4. Sleep more

When leptin falls, and ghrelin rises, hunger intensifies. Adequate sleep helps maintain their normal circadian rhythm, which keeps appetite and satiety signals stable.

Both hormones follow a circadian rhythm. Research by Yildiz et al. (2004) [4] shows that ghrelin and leptin reach their peak levels during sleep. This rhythmic pattern helps stabilise appetite and energy balance over a twenty-four-hour period.

Sleep restriction disrupts this hormonal balance. The study by Spiegel et al. (2004)[4] demonstrated the following changes when sleep was reduced:

• leptin levels decreased

• ghrelin levels increased

• appetite increased significantly

This shift creates a physiological environment that promotes stronger hunger signals and reduced satiety, which increases the likelihood of stress eating and intensifies hunger-related irritability.

To stabilise appetite and reduce the risk of hangry episodes:

- Maintain consistent sleep duration

- Aim for adequate nightly rest to support normal ghrelin and leptin rhythms

- Prioritise sleep during high-stress periods, since poor sleep further amplifies hormonal disruption

Hangry: Is This Something You Should Worry About?

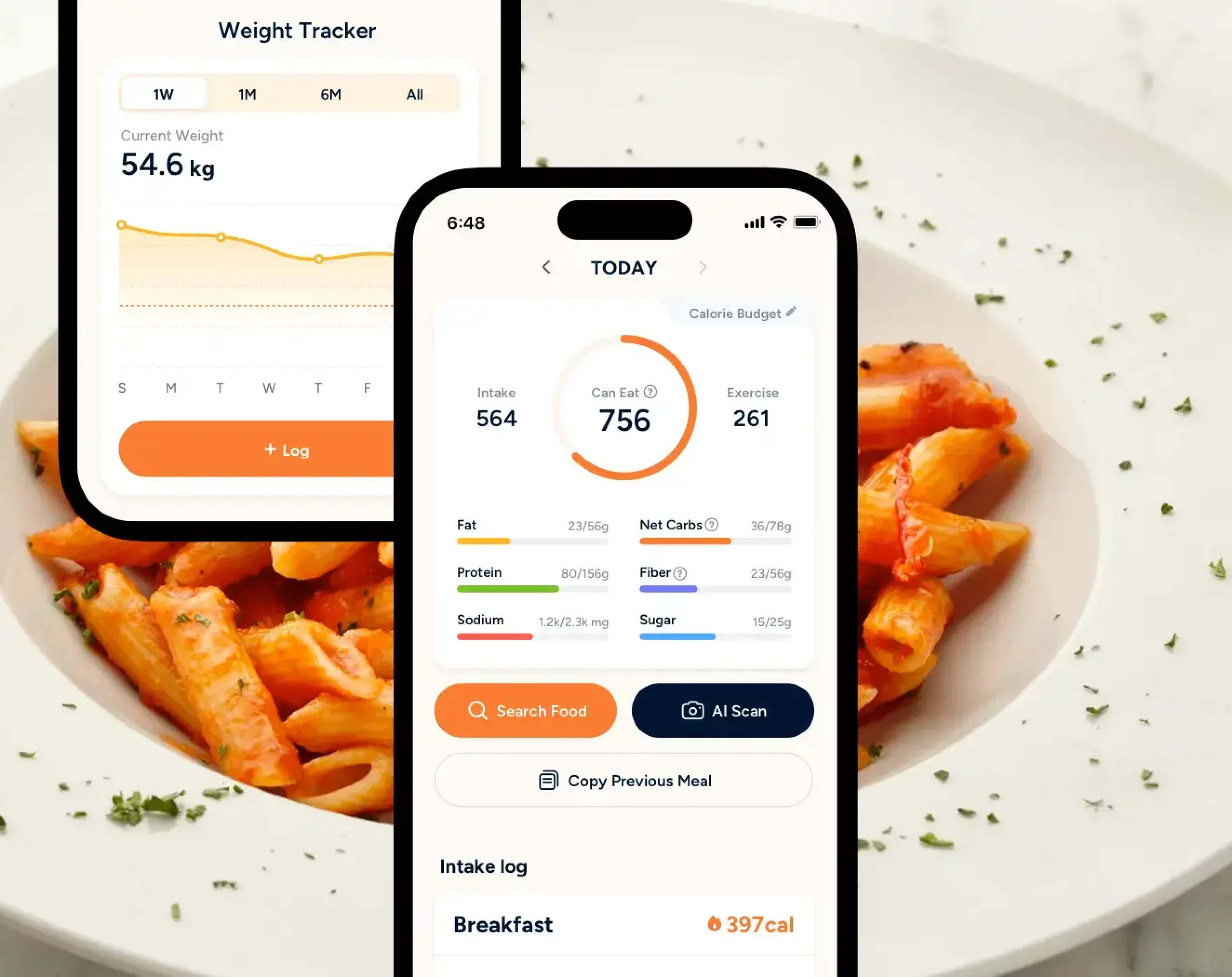

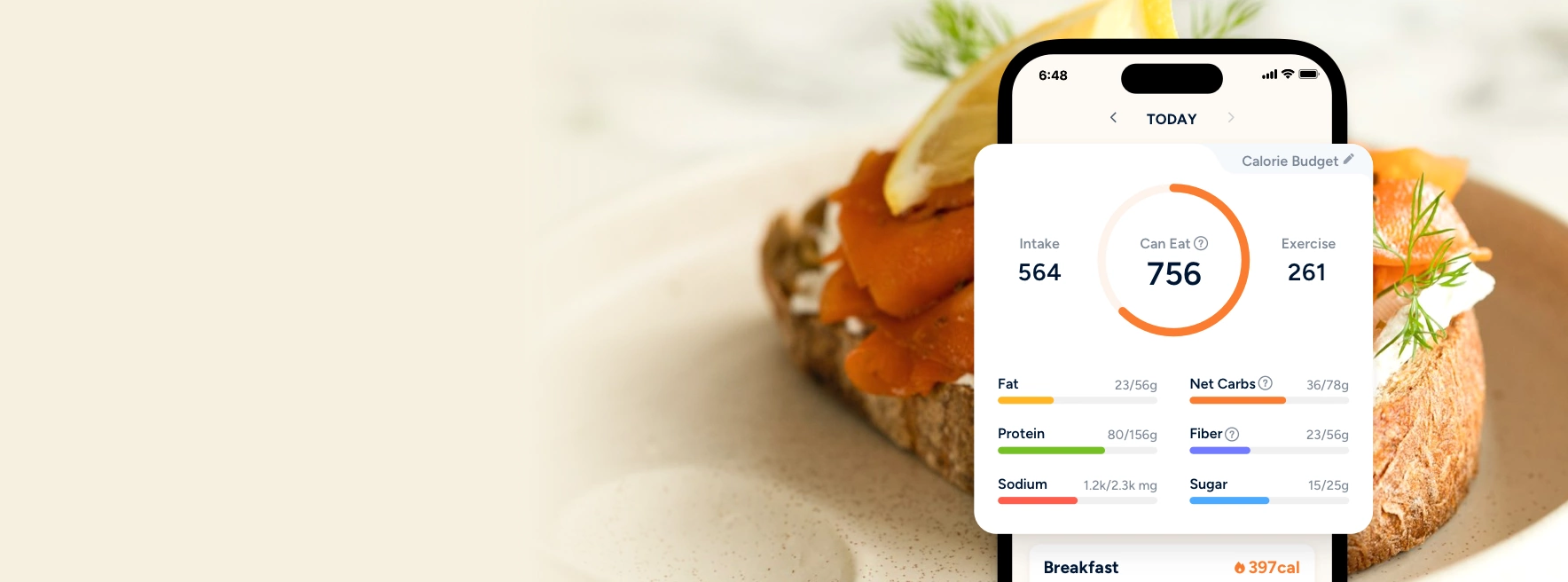

So what is hangry? Turns out, it is a very real phenomenon that happens to us when we are lacking food or are hungry in general. Being hangry, however, is relatively easy to alleviate, and you can do it by tracking your meals, calorie intake, and your mealtimes with Eato! Try it for free today.

Smarter Nutrition Tracking

Track calories and over 100 other nutrients all in one place.

Download Eato For Free